Menu

Welcome to the beautiful and diverse world of Louisiana irises. You will see stunning images throughout this site, but if you are starting here, you have come to an excellent place. There is much to discover and appreciate about these irises. From visionary leaders to passionate enthusiasts, many have shaped Louisiana Irises into what they are today. Join us on this journey and discover the stories behind the irises’ enduring legacy.

In the world of iris species, Louisiana irises are a distinct and significant minority. They consist of only five or six of around 300 species spread across the Northern Hemisphere. Irises occur in hot and cold climates, arid and wet situations, mountains and deserts, and under widely varying conditions in between.

Because the Louisiana iris species are cross-fertile and their offspring are not sterile, it was possible to develop a vast range of remarkably different hybrids. The name “Louisiana Irises” is popularly applied to them all, from the native species to the human-bredcultivars, but the wild species are the foundation and the place to start.

The following Milestones hit the high points, but we will introduce you to the broader story of these irises and provide links to the rich and engrossing details.

Click the images below to read more about each era in the history of the Louisiana Iris.

Click the images below to read more about each era in the history of the Louisiana Iris.

Medium height, 28 – 32”

Slightly zig-zag stalk

Shades of blue, sometimes darker; possibly white

Spoon shaped falls

Yellow-green foliage

Native to South Carolina, Georgia, Northern Florida

Relatively late bloomer

The British-born American botanist Thomas Walter described Iris hexagona in 1788 based on a specimen found near Charleston, South Carolina. Walter was first a merchant and rice farmer, but he became an accomplished botanist who focused on the plants growing within a 50-mile radius of his nearby home. I. hexagona was described in his book Flora Caroliniana. Walter is credited with naming over 200 species of plants. He was also an active supporter of the American Revolution.

Red – brick red, copper, rarely yellow

Medium height, 24 – 30”

Stalk often branches

Native to deltaic soils near rivers, streams, bayous

Occurs as far north as Illinois

Flowers small and drooping

Relative early bloomer

The second Louisiana iris to be named was the red Iris fulva, a sensation in the iris world in its day because of its unique color. I. fulva was collected on the banks of the Mississippi River near New Orleans by John Lyon, a Scottish-born botanist and plant collector in 1811. Lyon sent it to England, where another botanist, John Bellenden Ker-Gawler, published a description in Curtis Botanical Magazine in 1812.

Shades of blue, very rarely white

Short – 12 – 18”

Flowers bloom below top of foliage

Pronounced zig-zag stalk

Grow in wet soils but not standing water

Most likely LA iris to go dormant

Late bloomer

Grows as far north as Southern Ontario

The French cleric Abbé Claude Robin, a chaplain in the French Army in the American Revolution, first mentioned the third species described in this early period. Robin witnessed Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown in 1781 and later published three volumes on his travels in Louisiana, West Florida, and the West Indies between 1802 and 1806. In a section entitled Flore Louisinaise, Robin described I. brevicaulis and other plants he observed. This book was “translated, revised, and improved” by the botanist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, who published it as Florula Ludoviciana (Flora of Louisiana). The description of I. brevicaulis is usually credited to Rafinesque in 1817.

While thre eLouisiana iriss pecies were described in the early 1800s or shortly before, they hardly caused a ripple in the horticultural world. Each discovery was historically significant in retrospect but was essentially an isolated, noted-but-forgotten event. There was no recognition of the range of the plants or their relationship to other species in the iris world. In fact, no classification system for irises existed until William R. Dykes publishedThe Genus Iris in 1913, so the context into which to place these early discoveries did not yet exist.

Medium height, 28 – 32”

Slightly zig-zag stalk

Shades of blue, sometimes darker; possibly white

Spoon shaped falls

Yellow-green foliage

Native to South Carolina, Georgia, Northern Florida

Relatively late bloomer

The British-born American botanist Thomas Walter described Iris hexagona in 178 8based on a specimen found near Charleston, South Carolina. Walter wasf irst a merchant and rice farmer, but he became an accomplished botanist who focused on the plants growing within a 50-mile radius of his nearby home. I. hexagona was described in his book Flora Caroliniana. Walter is credited with naming over 200species of plants. He was also an active supporter of the American Revolution.

Red – brick red, copper, rarely yellow

Medium height, 24 – 30”

Stalk often branches

Native to deltaic soils near rivers, streams, bayous

Occurs as far north as Illinois

Flowers small and drooping

Relative early bloomer

The second Louisiana iris to be named was the red Iris fulva, a sensation in the iris world in its day because of its unique color. I. fulva was collected on the banks of the Mississippi River near New Orleans by John Lyon, a Scottish-born botanist and plant collector in 1811. Lyon sent it to England, where another botanist, John Bellenden Ker-Gawler, published a description in Curtis Botanical Magazine in 1812.

Shades of blue, very rarely white

Short – 12 – 18”

Flowers bloom below top of foliage

Pronounced zig-zag stalk

Grow in wet soils but not standing water

Most likely LA iris to go dormant

Late bloomer

Grows as far north as Southern Ontario

The French cleric Abbé Claude Robin, a chaplain in the French Army in the American Revolution, first mentioned the third species described in this early period. Robin witnessed Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown in 1781 and later published three volumes on his travels in Louisiana, West Florida, and the West Indies between 1802 and 1806. In a section entitled Flore Louisinaise, Robin described I. brevicaulis and other plants he observed. This book was “translated, revised, and improved” by the botanist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, who published it as Florula Ludoviciana (Flora of Louisiana). The description of I. brevicaulis is usually credited to Rafinesque in 1817.

So, what happened after the recognition of Irises hexagona, fulva, and brevicaulis? Nothing much for about a hundred years. By the 20th Century, these irises were in the paradoxical position of being described but unknown. While early botanists had recorded them, for all the horticultural world knew in 1900, they did not exist. They were not offered for sale or grown by name as garden plants.

There is little doubt that some who saw the irises growing around them in the distant past brought them into their gardens, although they may not have known what they were. It is also likely that native peoples used the plants, attracted to them for aesthetic or practical reasons. But it was not until the period of Modern Discovery in the early 1900s that we can document specific activity. From that point, advances have been consistent and cumulative.

On one occasion in the late 1860s, a single photograph attested to the irises’ presence. The New Orleans photographer Theodore Lilienthal, who focused primarily on the city’s architecture, took a picture published as “A View of the Swamps.” The image captures a massive field of irises in a cutover swamp somewhere in New Orleans. They were not identified as irises and did not represent or trigger early horticultural interest. Since development has destroyed all the wild irises in New Orleans, the photograph does testify to what has been lost and the need for preservation.

The earliest record of cultivation of the irises was when Mary Hutson Nelson of New Orleans introduced them into her garden in 1909. In 1920, the prominent Louisiana conservationist and artist Caroline Dormon discovered the irises near Morgan City and brought some back to Briarwood, her North Louisiana home. Mary Swords Debaillon of Lafayette, a well-known native plant enthusiast, built the most extensive garden featuring Louisiana irises. In New Orleans, Percy Viosca and Frank Carroll were important early collectors and activists. There were many more.

Thus, by the mid-1920s, an informal network of iris enthusiasts was in place in Louisiana. They had collected and shared plants, accumulated knowledge, and were a resource that would prove invaluable in the next phase of Louisiana iris history.

So, what happened after the recognition of Irises hexagona, fulva, and brevicaulis? Nothing much for about a hundred years. By the 20th Century, these irises were in the paradoxical position of being described but unknown. While early botanists had recorded them, for all the horticultural world knew in 1900, they did not exist. They were not offered for sale or grown by name as garden plants.

There is little doubt that some who saw the irises growing around them in the distant past brought them into their gardens, although they may not have known what they were. It is also likely that native peoples used the plants, attracted to them for aesthetic or practical reasons. But it was not until the period of Modern Discovery in the early 1900s that we can document specific activity. From that point, advances have been consistent and cumulative.

On one occasion in the late 1860s, a single photograph attested to the irises’ presence. The New Orleans photographer Theodore Lilienthal, who focused primarily on the city’s architecture, took a picture published as “A View of the Swamps.” The image captures a massive field of irises in a cutover swamp somewhere in New Orleans. They were not identified as irises and did not represent or trigger early horticultural interest. Since development has destroyed all the wild irises in New Orleans, the photograph does testify to what has been lost and the need for preservation.

The earliest record of cultivation of the irises was when Mary Hutson Nelson of New Orleans introduced them into her garden in 1909. In 1920, the prominent Louisiana conservationist and artist Caroline Dormon discovered the irises near Morgan City and brought some back to Briarwood, her North Louisiana home. Mary Swords Debaillon of Lafayette, a well-known native plant enthusiast, built the most extensive garden featuring Louisiana irises. In New Orleans, Percy Viosca and Frank Carroll were important early collectors and activists. There were many more.

Thus, by the mid-1920s, an informal network of iris enthusiasts was in place in Louisiana. They had collected and shared plants, accumulated knowledge, and were a resource that would prove invaluable in the next phase of Louisiana iris history.

Dr. John Small was a nationally known taxonomist and botanist who was the Head Curator of the New York Botanical Garden. Primarily working in Florida, by 1925, he had already published two editions of his Flora of the Southeastern States. His work in Louisiana set the stage for a historical leap in awareness of Louisiana irises.

The story of how Dr. Small discovered the irises in 1925, spotting them from a train as it passed through New Orleans, has been retold many times. It is a good story, but not true. After Small’s death in 1938, the botanist Dr. Edgar Wherry recounted the tale in a “Reminiscence” of his friend, colleague, and companion on the trip:

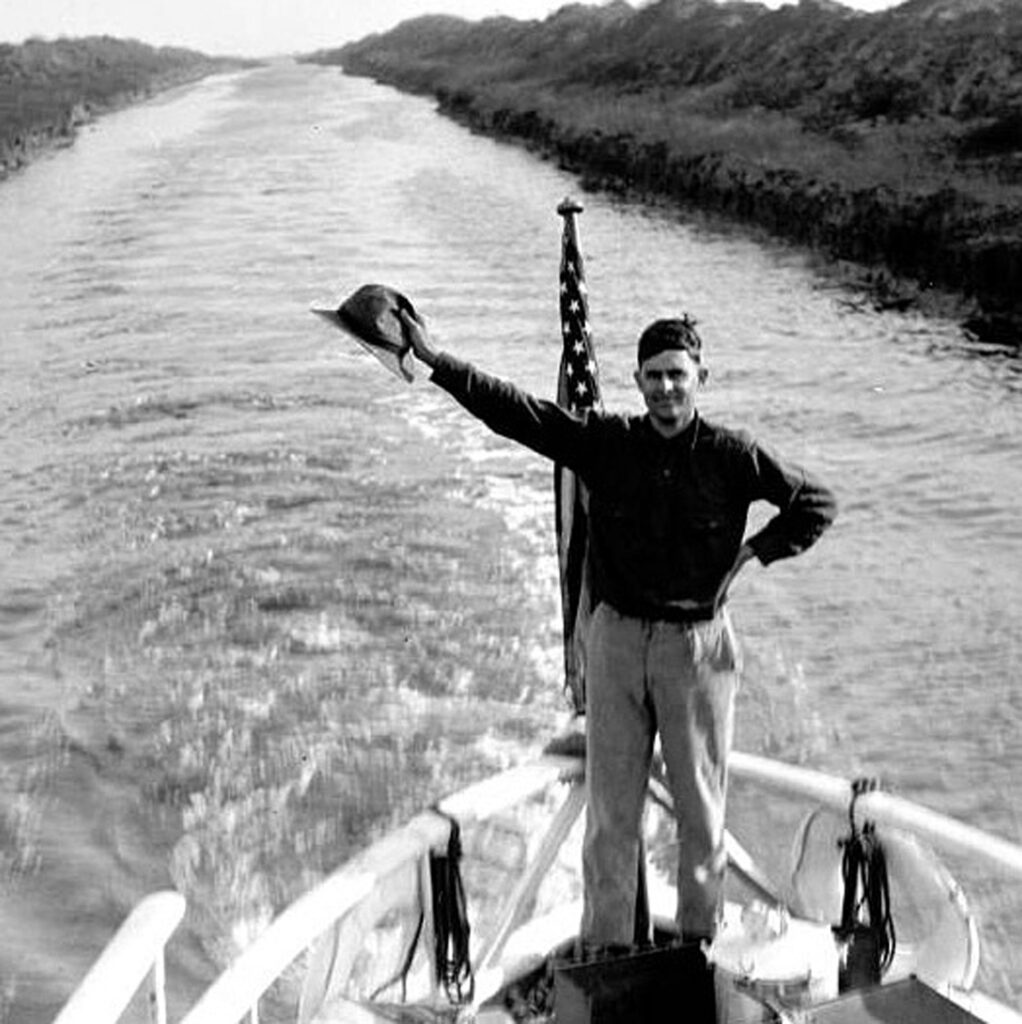

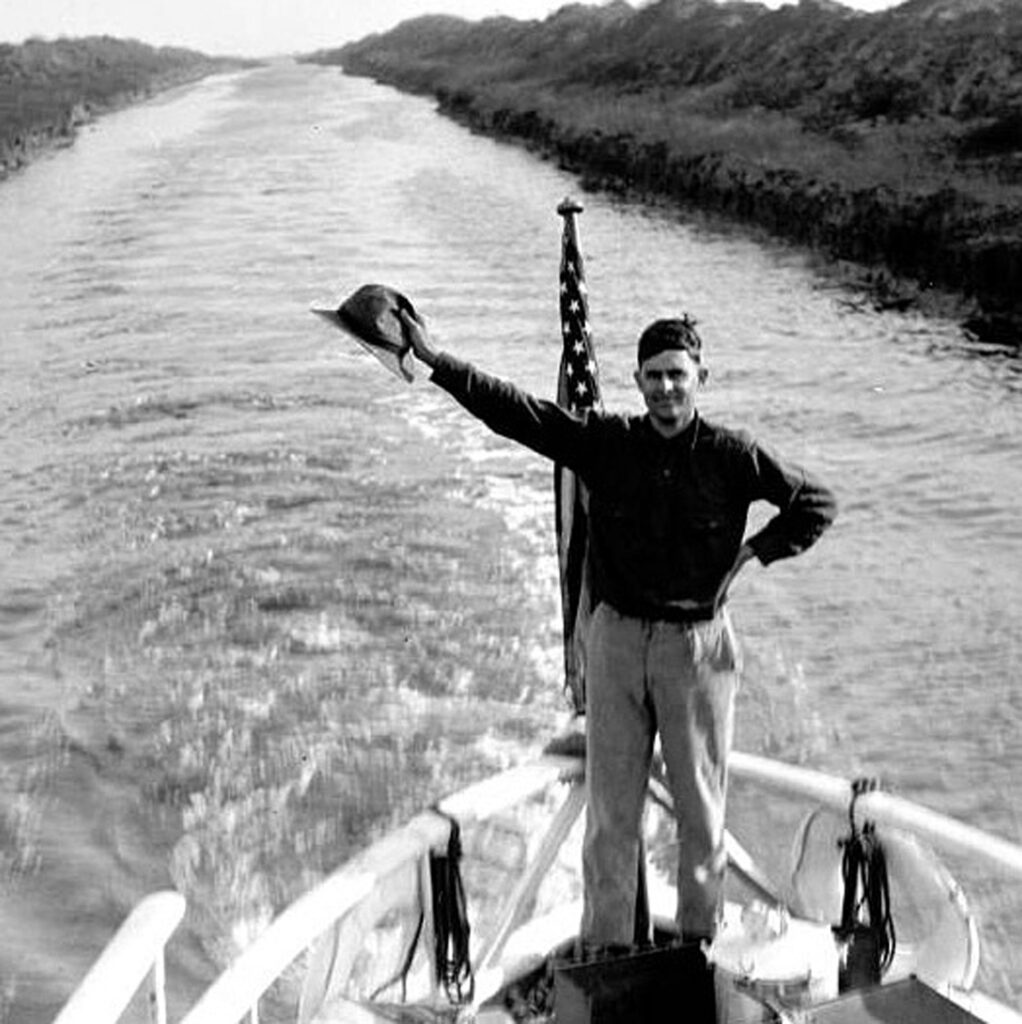

In those primitive days, there was no highway bridge from the east into New Orleans, autos being carried across Lake Pontchartrain by ferry boat…. As we started up from the ferry slip, a vast meadow of Irises attracted our attention. Small had told me in advance of the trip he had written to several Gulf State botanists inquiring about Irises, but they had all replied that there were either none at all nearby, or at most only a pale blue “Iris verisicolor.” Yet here, right along a main highway, there spread before our eyes a veritable rainbow.

To say that Small was hooked would be an understatement. He returned the next year and apparently every year until 1931 to explore, observe, and collect plants and seeds. He reportedly took 10,000 irises back to his “plantation” at the New York Botanical Garden so he could study them there.

Not knowing the area landscape, Small wisely connected with many of the people in the local “network” who had become aware of the irises and knew where to look. We don’t know Small’s full itinerary, but he searched all around New Orleans, the Northshore of Lake Pontchartrain, and downriver to the mouth of the Mississippi. He went west to around Houma but never explored the vast iris fields extending along the coast to Texas or found the Abbeville swamp, where a significant new species awaited discovery.

In 1925, Louisiana irises were primarily known only to the informal group of local native plant enthusiasts. But, by the early 1930s, the irises were recognized nationally in horticultural circles. Local officials celebrated the irises in Louisiana, especially New Orleans, thinking they had found a new natural resource, perhaps not rivaling oil and gas but still significant and unique to the area. A new organization, the Louisiana Iris Conservation Society, was formed to promote the irises. The organization planted iris gardens in public spaces in the city and named them for Louisiana poets and artists. School plantings were initiated and competitions held. The Mayor of New Orleans designated a “Louisiana Iris Day,” supposedly “in perpetuity.”

Most significantly, many individuals, excited by anticipated botanical treasures, trekked out to swampy areas to search for new irises, hoping to discover the next new species. A few years later, the Times-Picayune described this group as “amounting almost to a cult.” The ferver of this period receded eventually, but in its wake, the Louisiana iris joined many other well-known plants enjoyed in gardens across the country.

How can all this be attributed to Dr. Small? He should not get all the credit, but he and his work were the catalysts. Small did several things that captured people’s imagination.

Dr. Small’s career was made collecting, identifying, and describing native plants of all kinds. Before 1925, he had named iris species in Florida and continued that work in Louisiana. During his career, he and his associate E. J. Alexander described and named around 90 new species of irises. This was an extraordinary number, but adding emphasis, Small said in a 1932 talk in New Orleans, that there are “more than 100 species of iris represented by 300 color varieties … in and near New Orleans.” He contrasted that with the 18 previously recognized in all of North America ‒ a remarkable claim for one section of a single state.

Dr. Small spoke with authority. His credentials as a nationally respected botanist were impeccable. Even though he was prone to hyperbole, such as in describing the New Orleans area as “the iris center of the universe,” his exaggerations were a welcome message, and he was regarded as a man to be believed.

Dr. Small captured people’s imagination, and he garnered the attention of the horticultural world. Many took up the cause, and thanks mainly to his work, the obscurity of Louisiana irises was lifted.

Very tall – up to 7 feet in swamp

Flaring flower form – standards upright

Shades of blue, occasionally white

Straight stalk

Grows in wettest conditions of all Louisianas

Native to Gulf Coast wetlands from Mississippi to Texas

Relatively early bloomer

Tall

Open flower, somewhat flaring

Shades of blue, possibly white

Straight stalk

Grows in wet conditions

Native in coastal and peninsular Florida

Relatively early bloomer

Dr. John Small was a nationally known taxonomist and botanist who was the Head Curator of the New York Botanical Garden. Primarily working in Florida, by 1925, he had already published two editions of his Flora of the Southeastern States. His work in Louisiana set the stage for a historical leap in awareness of Louisiana irises.

The story of how Dr. Small discovered the irises in 1925, spotting them from a train as it passed through New Orleans, has been retold many times. It is a good story, but not true. After Small’s death in 1938, the botanist Dr. Edgar Wherry recounted the tale in a “Reminiscence” of his friend, colleague, and companion on the trip:

In those primitive days, there was no highway bridge from the east into New Orleans, autos being carried across Lake Pontchartrain by ferry boat…. As we started up from the ferry slip, a vast meadow of Irises attracted our attention. Small had told me in advance of the trip he had written to several Gulf State botanists inquiring about Irises, but they had all replied that there were either none at all nearby, or at most only a pale blue “Iris verisicolor.” Yet here, right along a main highway, there spread before our eyes a veritable rainbow.

To say that Small was hooked would be an understatement. He returned the next year and apparently every year until 1931 to explore, observe, and collect plants and seeds. He reportedly took 10,000 irises back to his “plantation” at the New York Botanical Garden so he could study them there.

Not knowing the area landscape, Small wisely connected with many of the people in the local “network” who had become aware of the irises and knew where to look. We don’t know Small’s full itinerary, but he searched all around New Orleans, the Northshore of Lake Pontchartrain, and downriver to the mouth of the Mississippi. He went west to around Houma but never explored the vast iris fields extending along the coast to Texas or found the Abbeville swamp, where a significant new species awaited discovery.

In 1925, Louisiana irises were primarily known only to the informal group of local native plant enthusiasts. But, by the early 1930s, the irises were recognized nationally in horticultural circles. Local officials celebrated the irises in Louisiana, especially New Orleans, thinking they had found a new natural resource, perhaps not rivaling oil and gas but still significant and unique to the area. A new organization, the Louisiana Iris Conservation Society, was formed to promote the irises. The organization planted iris gardens in public spaces in the city and named them for Louisiana poets and artists. School plantings were initiated and competitions held. The Mayor of New Orleans designated a “Louisiana Iris Day,” supposedly “in perpetuity.”

Most significantly, many individuals, excited by anticipated botanical treasures, trekked out to swampy areas to search for new irises, hoping to discover the next new species. A few years later, the Times-Picayune described this group as “amounting almost to a cult.” The ferver of this period receded eventually, but in its wake, the Louisiana iris joined many other well-known plants enjoyed in gardens across the country.

How can all this be attributed to Dr. Small? He should not get all the credit, but he and his work were the catalysts. Small did several things that captured people’s imagination.

Dr. Small’s career was made collecting, identifying, and describing native plants of all kinds. Before 1925, he had named iris species in Florida and continued that work in Louisiana. During his career, he and his associate E. J. Alexander described and named around 90 new species of irises. This was an extraordinary number, but adding emphasis, Small said in a 1932 talk in New Orleans, that there are “more than 100 species of iris represented by 300 color varieties … in and near New Orleans.” He contrasted that with the 18 previously recognized in all of North America ‒ a remarkable claim for one section of a single state.

Small arranged for the New York Botanical Garden artist Mary Eaton to paint beautiful, botanically correct watercolors of many of the new species, and color plates were printed in the Garden’s publication Addisonia. The images were a sensation at a time when color printing was in its infancy. These paintings alone probably did more to alert the horticultural world to the new irises than anything else that Dr. Small did.

Small promoted the irises in talks, letters, and articles. He did not give talks that often, but he was armed with “lantern slides” that showed the irises in color. He was a regular and generous correspondent, exchanging letters with local iris and native plant enthusiasts and often sending plants and seeds of various kinds. He wrote many articles for the Journal of the New York Botanical Garden, several warning that the irises’ habitat was seriously endangered even at that early date.

Dr. Small spoke with authority. His credentials as a nationally respected botanist were impeccable. Even though he was prone to hyperbole, such as in describing the New Orleans area as “the iris center of the universe,” his exaggerations were a welcome message, and he was regarded as a man to be believed.

Dr. Small captured people’s imagination, and he garnered the attention of the horticultural world. Many took up the cause, and thanks mainly to his work, the obscurity of Louisiana irises was lifted.

Very tall – up to 7 feet in swamp

Flaring flower form – standards upright

Shades of blue, occasionally white

Straight stalk

Grows in wettest conditions of all Louisianas

Native to Gulf Coast wetlands from Mississippi to Texas

Relatively early bloomer

Tall

Open flower, somewhat flaring

Shades of blue, possibly white

Straight stalk

Grows in wet conditions

Native in coastal and peninsular Florida

Relatively early bloomer

Dr. Small helped usher in an “Era of Collecting” that lasted over a decade. He vividly demonstrated the massive variety in colors and forms that were “out there,” almost in our backyards, it seemed. Having been made aware of these treasures, many had to have them. The irises were years away from being available in commerce, so a trip to the wetlands was the only option. No doubt boots were required, but many wet areas, while perhaps snakey, did not involve deep water, waders, or the danger of alligators. A few went all in.

There is no way to know how many irises came from the wild into gardens. Where are they now? A few old, identifiable irises remain available, but almost all are lost. Gardens rarely endure, and identifying information is almost invariably lost even when plants survive. Even public gardens have not proven reliable stewards to preserve specific plants across generations.

To a large extent, the best old collected irises probably disappeared into the gene pool of hybrid irises, and their legacy lives on in modern cultivars. It certainly is the case that the phenomenal variety of colors represented in newer irises today owes an enormous debt to the remarkable and colorful array found in species forms and natural hybrids. Without the work of the collectors who essentially assembled the breeding stock, today’s irises would be a pale shadow of what they are.

But given today’s sensitivity to environmental issues, was the Era of Collecting something to celebrate? Small himself was among the first to sound the alarm about habitat destruction. He dramatically conveyed that the irises were endangered. In his article, “Salvaging the Native American Iris,” Small wrote in 1932:

“After a thorough survey of the iris lands in the New Orleans region, we confidently calculate that through rural improvements and urban growth, about eighty percent of the iris fields of a half-century ago have been ravaged or destroyed!”

If that seems terrible, forty years later, in 1993, and adding insult to injury, Joseph Mertzweiller said that “wild populations are now estimated at less than 10 percent of what they were in 1930.” We have doubled down on iris destruction.

Did the iris collectors of the 1930s contribute to this dire decline? Hardly. While a few early dealers may have inappropriately harvested irises to an unethical extent, the average collector did not. Had they passed over an unusual form in the wild, the plant likely would have succumbed to saltwater intrusion, roadside herbicide, agriculture, urban development, canal dredging, or other human and natural activities that have so significantly diminished the wild iris populations. We owe a huge debt of gratitude to the past iris collectors who captured the wild irises’ genetic diversity even though specific plants eventually disappeared. Today, there is elevated recognition of the need to preserve individual forms of the wild irises, and the SLI Species Preservation Project was created for this purpose.

Dr. Small helped usher in an “Era of Collecting” that lasted over a decade. He vividly demonstrated the massive variety in colors and forms that were “out there,” almost in our backyards, it seemed. Having been made aware of these treasures, many had to have them. The irises were years away from being available in commerce, so a trip to the wetlands was the only option. No doubt boots were required, but many wet areas, while perhaps snakey, did not involve deep water, waders, or the danger of alligators. A few went all in.

There is no way to know how many irises came from the wild into gardens. Where are they now? A few old, identifiable irises remain available, but almost all are lost. Gardens rarely endure, and identifying information is almost invariably lost even when plants survive. Even public gardens have not proven reliable stewards to preserve specific plants across generations.

To a large extent, the best old collected irises probably disappeared into the gene pool of hybrid irises, and their legacy lives on in modern cultivars. It certainly is the case that the phenomenal variety of colors represented in newer irises today owes an enormous debt to the remarkable and colorful array found in species forms and natural hybrids. Without the work of the collectors who essentially assembled the breeding stock, today’s irises would be a pale shadow of what they are.

But given today’s sensitivity to environmental issues, was the Era of Collecting something to celebrate? Small himself was among the first to sound the alarm about habitat destruction. He dramatically conveyed that the irises were endangered. In his article, “Salvaging the Native American Iris,” Small wrote in 1932:

“After a thorough survey of the iris lands in the New Orleans region, we confidently calculate that through rural improvements and urban growth, about eighty percent of the iris fields of a half-century ago have been ravaged or destroyed!”

If that seems terrible, forty years later, in 1993, and adding insult to injury, Joseph Mertzweiller said that “wild populations are now estimated at less than 10 percent of what they were in 1930.” We have doubled down on iris destruction.

Did the iris collectors of the 1930s contribute to this dire decline? Hardly. While a few early dealers may have inappropriately harvested irises to an unethical extent, the average collector did not. Had they passed over an unusual form in the wild, the plant likely would have succumbed to saltwater intrusion, roadside herbicide, agriculture, urban development, canal dredging, or other human and natural activities that have so significantly diminished the wild iris populations. We owe a huge debt of gratitude to the past iris collectors who captured the wild irises’ genetic diversity even though specific plants eventually disappeared. Today, there is elevated recognition of the need to preserve individual forms of the wild irises, and the SLI Species Preservation Project was created for this purpose.

The work of Dr.Small in discovering the wide range of irises in Louisiana was of enduring importance, but his naming of species was not. Some taxonomists and botanists at the time must have raised their eyebrows at the announced discovery of such a large number of species in a relatively small area. It was five times greater than the number previously named in all of North America.

In 1935, Percy Viosca, long a student of the flora of Southeast Louisiana, published a paper asserting that only three distinct iris species of the Louisiana iris group existed in the area. Viosca’s view, which prevails today, was that the “large majority of the forms described from the same region by Small and Alexander … and innumerable others yet undescribed, [should be interpreted] in part as variants and in part as natural hybrids.”

Visosca’s view is accepted today, and almost all but one of Small’s species names for irises he discovered in Louisiana have been abandoned. Only Iris giganticaerulea is still used. Among irises he found in Florida, only Iris savannarum is still recognized, although it is possible that a couple of others may be revived.

Dr. Small’s botanical descriptions were meticulous and detailed, but he was often quick to apply a species name to a new find. While he acknowledged that some might be natural hybrids, he aggressively promoted them to species rank without further study. Regardless of the controversy over nomenclature, the impact of Dr. Small’s work has endured, and he deserves credit for elevating the Louisiana iris to botanical prominence.

The work of Dr.Small in discovering the wide range of irises in Louisiana was of enduring importance, but his naming of species was not. Some taxonomists and botanists at the time must have raised their eyebrows at the announced discovery of such a large number of species in a relatively small area. It was five times greater than the number previously named in all of North America.

In 1935, Percy Viosca, long a student of the flora of Southeast Louisiana, published a paper asserting that only three distinct iris species of the Louisiana iris group existed in the area. Viosca’s view, which prevails today, was that the “large majority of the forms described from the same region by Small and Alexander … and innumerable others yet undescribed, [should be interpreted] in part as variants and in part as natural hybrids.”

Visosca’s view is accepted today, and almost all but one of Small’s species names for irises he discovered in Louisiana have been abandoned. Only Iris giganticaerulea is still used. Among irises he found in Florida, only Iris savannarum is still recognized, although it is possible that a couple of others may be revived.

Dr. Small’s botanical descriptions were meticulous and detailed, but he was often quick to apply a species name to a new find. While he acknowledged that some might be natural hybrids, he aggressively promoted them to species rank without further study. Regardless of the controversy over nomenclature, the impact of Dr. Small’s work has endured, and he deserves credit for elevating the Louisiana iris to botanical prominence.

In 1938, while exploring near his Abbeville, Louisiana, home, W. B. MacMillan encountered masses of tall red irises in a few square miles of cypress-tupelo swamp. They were red like I. fulva but distinctively tall like I. giganticaerulea. The reds were considered more vivid than in fulva, and the flowers were much larger. The form generally drooped like fulva, but the floral parts were wider.

At the time, no one knew how to classify these plants. They were referred to as “super fulvas” or, more often, as the “Abbeville Reds.” Although other species grew in the vicinity, none occurred in the Abbeville swamp, which was then the exclusive turf of the Abbeville Reds (and an occasional yellow). After years of study by Lowell Fitz Randolph, a Cornell University geneticist, and Ira S. Nelson, a Horticulture professor at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (its current name), the irises were designated I. nelsonii in 1966. The name honors Ira Nelson, who was tragically killed in an automobile accident the year before.

Amateur iris hybridizers did not waste time using the Abbeville Reds in their crosses, and MacMillan, Nelson, Caroline Dormon, and others began achieving excellent results.

Red like fulva, tall like giganticaerule

Larger flowers than fulva and often a “redder” color

Rarely yellow

Grows in a few square miles of cypress-tupelo swamp near Abbeville, LA

Stalk slightly zig-zag

Inconspicuous signal

Tubular styles

In 1938, while exploring near his Abbeville, Louisiana, home, W. B. MacMillan encountered masses of tall red irises in a few square miles of cypress-tupelo swamp. They were red like I. fulva but distinctively tall like I. giganticaerulea. The reds were considered more vivid than in fulva, and the flowers were much larger. The form generally drooped like fulva, but the floral parts were wider.

At the time, no one knew how to classify these plants. They were referred to as “super fulvas” or, more often, as the “Abbeville Reds.” Although other species grew in the vicinity, none occurred in the Abbeville swamp, which was then the exclusive turf of the Abbeville Reds (and an occasional yellow). After years of study by Lowell Fitz Randolph, a Cornell University geneticist, and Ira S. Nelson, a Horticulture professor at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (its current name), the irises were designated I. nelsonii in 1966. The name honors Ira Nelson, who was tragically killed in an automobile accident the year before.

Amateur iris hybridizers did not waste time using the Abbeville Reds in their crosses, and MacMillan, Nelson, Caroline Dormon, and others began achieving excellent results.

Red like fulva, tall like giganticaerule

Larger flowers than fulva and often a “redder” color

Rarely yellow

Grows in a few square miles of cypress-tupelo swamp near Abbeville, LA

Stalk slightly zig-zag

Inconspicuous signal

Tubular styles

By 1941, interest in Louisiana irises had risen to a new level. Beyond a desire to locate new and beautiful garden plants, collectors and iris activists became interested in organizing to promote, preserve, and develop these plants.

Ira S. Nelson, then a relatively new Professor of Horticulture at the University in Lafayette, led the way, along with W. B. MacMillan of Abbeville, the first president of the new organization, which was first named the Mary Swords Debaillon Iris Society. The University heavily supported the Society, supplying space for meetings, test gardens, and other activities.

The new Society embarked on an ambitious agenda. It held annual meetings, collecting trips to the swamps, and elaborately staged shows. In cooperation with the American Iris Society, the organization created a top award for Louisiana irises, now called the Mary Swords Debaillon Medal.

The Society quickly began to produce excellent publications, one of its most outstanding achievements. From the earliest days, the Society published Bulletins, and then, after about ten years, the SLI Newsletter. The newsletter evolved into a quarterly magazine that continues today as the Fleur de Lis. The Fleur compares favorably with the publications of any comparable organization.

The Society also produced “Special Publications,” a series of occasional, high-quality booklets with articles on various topics of iris interest. It also has published two editions of a definitive book on Louisiana irises, the most recent in 2000 entitled The Louisiana Iris: The Taming of a Native American Wildflower. A website was created in xxxx, updated significantly in xxxx, and was redesigned in 2024.

At its birth, the new Society represented a joining of people who had been actively discovering and working with the native irises and who wished to organize to achieve new objectives. Its membership was predominantly in Louisiana, but a significant Texas contingent participated in the early days. People around the country joined the new group, but it had the flavor of a local organization. The Society held conventions in its birthplace of Lafayette for sixty years before rotating to cities such as Little Rock, Dallas, Shreveport, Tucson, and New Orleans. Today, the Society is a national and international plant society, an independent, nonprofit organization that functions as a Section of the American Iris Society. Membership, while still heavily tilted to Louisiana and Texas, has broadened across the country.

By 1941, interest in Louisiana irises had risen to a new level. Beyond a desire to locate new and beautiful garden plants, collectors and iris activists became interested in organizing to promote, preserve, and develop these plants.

Ira S. Nelson, then a relatively new Professor of Horticulture at the University in Lafayette, led the way, along with W. B. MacMillan of Abbeville, the first president of the new organization, which was first named the Mary Swords Debaillon Iris Society. The University heavily supported the Society, supplying space for meetings, test gardens, and other activities.

The new Society embarked on an ambitious agenda. It held annual meetings, collecting trips to the swamps, and elaborately staged shows. In cooperation with the American Iris Society, the organization created a top award for Louisiana irises, now called the Mary Swords Debaillon Medal.

The Society quickly began to produce excellent publications, one of its most outstanding achievements. From the earliest days, the Society published Bulletins, and then, after about ten years, the SLI Newsletter. The newsletter evolved into a quarterly magazine that continues today as the Fleur de Lis. The Fleur compares favorably with the publications of any comparable organization.

The Society also produced “Special Publications,” a series of occasional, high-quality booklets with articles on various topics of iris interest. It also has published two editions of a definitive book on Louisiana irises, the most recent in 2000 entitled The Louisiana Iris: The Taming of a Native American Wildflower. A website was created in xxxx, updated significantly in xxxx, and was redesigned in 2024.

At its birth, the new Society represented a joining of people who had been actively discovering and working with the native irises and who wished to organize to achieve new objectives. Its membership was predominantly in Louisiana, but a significant Texas contingent participated in the early days. People around the country joined the new group, but it had the flavor of a local organization. The Society held conventions in its birthplace of Lafayette for sixty years before rotating to cities such as Little Rock, Dallas, Shreveport, Tucson, and New Orleans. Today, the Society is a national and international plant society, an independent, nonprofit organization that functions as a Section of the American Iris Society. Membership, while still heavily tilted to Louisiana and Texas, has broadened across the country.

© 2024 Society for Louisiana Irises. All rights reserved.